When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

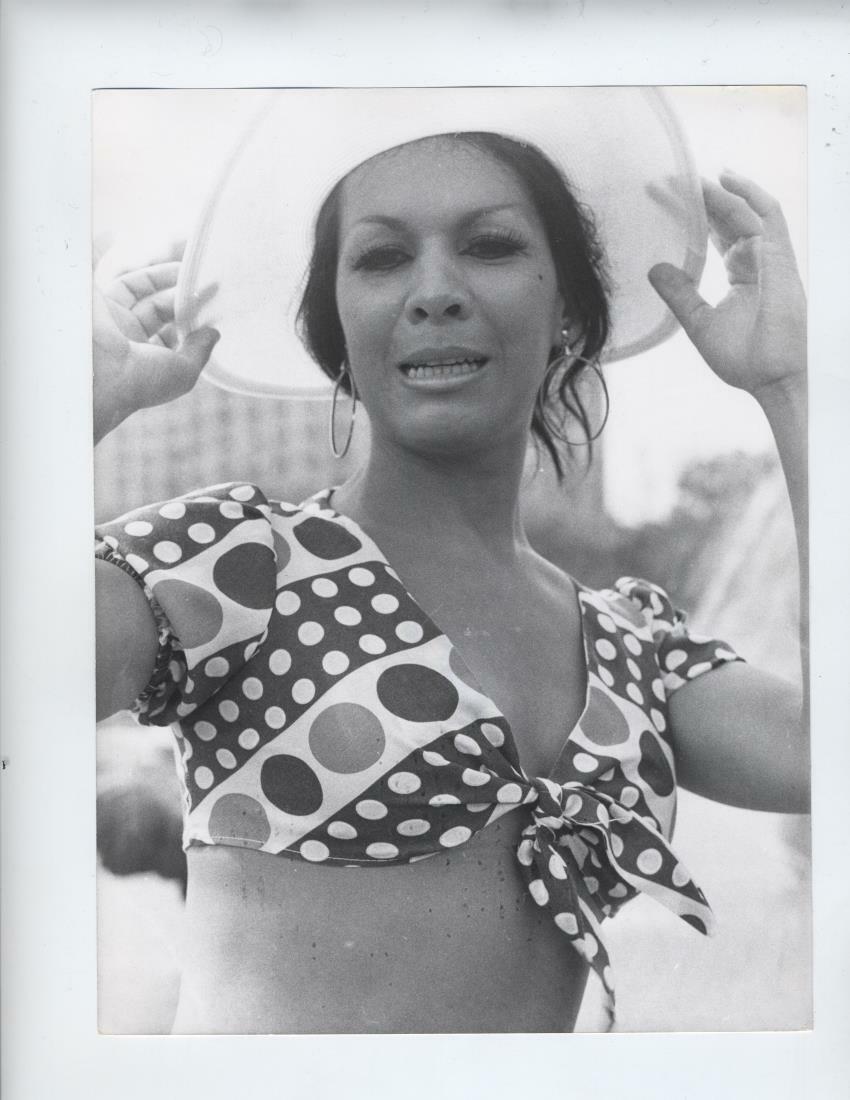

A great 7 1/4 x 9 1/2 inch vintage original photo of Maria Montez in her debut in Folies Bergere

The Folies Bergère (French pronunciation: [fɔ.li bɛʁ.ʒɛʁ]) is a cabaret music hall, located in Paris, France. Located at 32 Rue Richer in the 9th Arrondissement, the Folies Bergère was built as an opera house by the architect Plumeret. It opened on 2 May 1869 as the Folies Trévise, with light entertainment including operettas, comic opera, popular songs, and gymnastics. It became the Folies Bergère on 13 September 1872, named after nearby Rue Bergère. The house was at the height of its fame and popularity from the 1890s' Belle Époque through the 1920s.

Revues featured extravagant costumes, sets and effects, and often nude women. In 1926, Josephine Baker, an African-American expatriate singer, dancer and entertainer, caused a sensation at the Folies Bergère by dancing in a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas and little else.

The institution is still in business, and is still a strong symbol of French and Parisian life.Contents1 History2 Performers3 Filmography4 Similar venues5 In popular culture6 See also7 Notes8 External linksHistory

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Jules Chéret, Folies Bergère, Fleur de Lotus, 1893 Art Nouveau poster for the Ballet Pantomime

Costume, c. 1900Located at 32 Rue Richer in the 9th Arrondissement, the Folies Bergère was built as an opera house by the architect Plumeret. The métro stations are Cadet and Grands Boulevards.

It opened on 2 May 1869[citation needed] as the Folies Trévise, with light entertainment including operettas, opéra comique (comic opera), popular songs, and gymnastics. It became the Folies Bergère on 13 September 1872, named after a nearby street, Rue Bergère ("bergère" means "shepherdess").[1]Édouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882In 1882, Édouard Manet painted his well-known painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère which depicts a bar-girl, one of the demimondaines, standing before a mirror.

In 1886, Édouard Marchand conceived a new genre of entertainment for the Folies Bergère: the music-hall revue. Women would be the heart of Marchand's concept for the Folies. In the early 1890s, the American dancer Loie Fuller starred at the Folies Bergère. In 1902, illness forced Marchand to leave after 16 years.[2]Josephine Baker in a banana skirt from the Folies Bergère production Un Vent de FolieIn 1918, Paul Derval [fr] (1880–1966) made his mark on the revue. His revues featured extravagant costumes, sets and effects, and "small nude women". Derval's small nude women would become the hallmark of the Folies. During his 48 years at the Folies, he launched the careers of many French stars including Maurice Chevalier, Mistinguett, Josephine Baker, Fernandel and many others. In 1926, Josephine Baker, an African-American ex-patriate singer, dancer and entertainer, caused a sensation at the Folies Bergère in a new revue, La Folie du Jour, in which she danced a number Fatou wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas and little else. Her erotic dancing and near-nude performances were renowned. The Folies Bergère catered to popular taste. Shows featured elaborate costumes; the women's were frequently revealing, practically leaving them naked, and shows often contained a good deal of nudity. Shows also played up the "exoticness" of people and objects from other cultures, obliging the Parisian fascination with the négritude of the 1920s.[clarification needed]

In 1926 the facade of the theatre was given a complete make-over by the artist Maurice Pico [fr]. The facade was redone in Art Deco style, one of the many Parisian theatres of this period using the style.[3]

In 1936, Derval brought Josephine Baker from New York City to lead the revue En Super Folies. Michel Gyarmathy [de], a young Hungarian arrived from Balassagyarmat, his hometown, designed the poster for En Super Folies, a show starring Josephine Baker in 1936. This began a long love story between Michel Gyarmathy, Paris, the Folies Bergère and the public of the whole world which lasted 56 years. The funeral of Paul Derval was held on 20 May 1966. He was 86 and had reigned supreme over the most celebrated music hall in the world. His wife Antonia, supported by Michel Gyarmathy, succeeded him. In August 1974, the Folies Antonia Derval passed on the direction of the business to Hélène Martini, the empress of the night (25 years earlier she had been a showgirl in the revues). This new mistress of the house reverted to the original concept to maintain the continued existence of the last music hall which remained faithful to the tradition.

Since 2006, the Folies Bergère has presented some musical productions with Stage Entertainment like Cabaret (2006–2008) or Zorro (2009–2010).

PerformersCharles AznavourLouisa Baïleche, dancer and singerJosephine BakerPierre BoulezAimée CamptonCantinflasCharlie ChaplinMaurice ChevalierDalidaNorma Duval, Spanish actress and starFernandelW. C. FieldsElla FitzgeraldEugénie FougèreLoie FullerJean GabinGeorges GuetaryGrock, clownSuzy van HallJohnny HallydayBenny HillZizi JeanmaireElton JohnMargaret Kelly Leibovici, founder of the Bluebell GirlsValérie LemercierClaudine LongetJean MaraisMarcel MarceauCléo de MérodeMistinguettGilbert MontagneYves MontandLiliane MontevecchiKara, Gentleman JugglerMusidoraNala Damajanti, snake charmerLa Belle OteroPatachouÉdith PiafLiane de PougyYvonne PrintempsRaimuRégineLine RenaudGinger RogersFrank SinatraLittle TichCharles TrenetOdette ValerySylvie VartanGregory BelliniRy XFilmography1935: Folies Bergère de Paris directed by Roy Del Ruth, with Maurice Chevalier, Merle Oberon, and Ann Sothern1935: Folies Bergère de Paris directed by Marcel Achard with Maurice Chevalier, Natalie Paley, Fernand Ledoux. A French-language version of the 1935 Hollywood film.1956: Folies-Bergère directed by Henri Decoin with Eddie Constantine, Zizi Jeanmaire, Yves Robert, Pierre Mondy1956: Énigme aux Folies Bergère directed by Jean Mitry with Dora Doll, Claude Godard1991: La Totale! directed by Claude Zidi with Thierry LhermitteSimilar venuesThe Folies Bergère inspired the Ziegfeld Follies in the United States and other similar shows, including a long-standing revue, the Las Vegas Folies Bergere, at the Tropicana Resort & Casino in Las Vegas and the Teatro Follies in Mexico.

In the 1930s and '40s the impresario Clifford C. Fischer staged several Folies Bergere productions in the United States. These included the Folies Bergère of 1939 at the Broadway Theater in New York[4] and the Folies Bergère of 1944 at the Winterland Ballroom[5][6] in San Francisco.

The Las Vegas Folies Bergere, which opened in 1959, closed at the end of March 2009 after nearly 50 years in operation.[7][8][9]

A recent example is Faceboyz Folliez, a monthly burlesque and variety show at the Bowery Poetry Club in New York City.[10][11]

In popular cultureIn Richard Connell's 1924 short story "The Most Dangerous Game", General Zaroff "hummed a snatch of song from the 'Folies Bergere'" when referring to the pack of dogs he released to patrol the grounds every night.It is the setting for the 1934 ballet Bar aux Folies-Bergère with choreography by Ninette de Valois to music by Chabrier.In the 1954 film The Last Time I Saw Paris, when a man innocently looks at a baby right after her bath, her grandfather covers the baby's body with a towel and tells the man (her uncle-in-law) that this is not the Folies-Bergère.In the 1960s, British science fiction TV series Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons episode "Model Spy", Colonel White remarks that Cloudbase is an operational base and not the Folies Bergère.In the 1960s, British science fiction TV series Thunderbirds episode "The Perils of Penelope" Alan Tracy expresses disappointment at not being able to accompany his brothers to "The Folies". Lady Penelope tells him he is too young.In the beginning of Episode 2.20 of the crime drama series Vega$ "The Golden Gate Cop Killer: Part 1" an advertisement for Foiles Bergere can be seen several times on the Tropicana's sign as various characters pull up to the front and exit their vehicles.In the 1982 musical Nine, the character of Liliane La Fleur sings a song titled "Folies Bergère" in homage to the Folies Bergère and similar musical acts.In the 1984 musical Sunday in the Park with George, George promises to take Dot to the Follies.[12]In the 1990s, British comedy series Knowing Me Knowing You with Alan Partridge, fictional TV chat show host Alan Partridge's guests and co-presenter attend the Folies Bergere on the evening before the show's live broadcast from Paris. The show's Band Leader, Glen Ponder, is sacked by Partridge live on air for not inviting him on the trip.It is mentioned in the Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room attraction at Disneyland in Anaheim, California by the character "Fritz".It is mentioned in Allan Sherman’s song "You Went the Wrong Way, Old King Louie."See alsoAbsintheCabaret Red LightCasino de ParisCrazy Horse (cabaret)Jubilee!Le LidoMoulin RougeParadis LatinPeepshowSirens of TITropicana Club

A Brief History of the Folies-Bergère

"The Folies-Bergères [sic] , rue Richter 32, near the Boulevard Montmartre, a very popular resort... visitors take seats where thy please, or promenade in the galleries, while musical, dramatic and conjuring performances are given on the stage. Admission 2Fr"

Baedeker, Paris and Its Environs, 1878Quoted by T. J. Clark

The Folies-Bergère was the first music-hall to be opened in Paris. It was conceived in conscious imitation of the Alhambra in London, a music hall known and much-loved for broad comedy, opera, ballet and circus.

The Folies-Bergère was supposed to be the Folies Trevise, because it was on the corner of the rue Richter and the rue Trevise. The Duc de Trevise would not allow his name to be brought into such potential ill-repute. The rue Bergère, a road named after a master dyer, was a block or so away. 'Folies' came from the Latin, foliae, meaning 'leaves' but transmogrified into 'field' and thence to a place for open-air entertainment.

The Folies-Bergère opened in May 1869, not far from the heart of the post-Haussmann cultural centre of Paris, south of Montmartre, a little east of the boulevard des Italiens (known simply as The Boulevard). Entry cost 2 francs for an unreserved seat.

In November 1871, following the considerable interruptions of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, the theatre was taken over by Leon Sari, who remodelled the auditorium, put in the famous promenade, and installed a 'garden' with a large central fountain.

A Folies-Bergère show typically included ballet, acrobatics, pantomime, operetta, animal acts, many including spectacular special effects. However, the Folies-Bergère was perhaps more well-known for its sensual allures, as described by Huysmans and Maupassant.

The women of the promenoir were required to demonstrate discretion; none were allowed in without fortnightly-renewable cards issued by the management. This arrangement lasted until 1918.

Artists and writers were drawn to the Folies-Bergère and establishments like it not least because they were fascinating venues for the practice of social anthropology, where different classes met in an environment in which strict bourgeois morality held no sway whatsoever. Manet's picture features his friends - artists and models; it is the kind of fashionable place in which he spent his evenings.

Folies-Bergère, Parisian music hall and variety-entertainment theatre that is one of the major tourist attractions of France. Following its opening in a new theatre on May 1, 1869, the Folies became one of the first major music halls in Paris. During its early years it presented a mixed program of operetta and pantomime, with the renowned mime Pierre Legrand performing the latter.

In 1887 the Folies’ highly popular revue entitled “Place aux Jeunes” established it as the premiere nightspot in Paris. By the last decade of the 19th century, the theatre’s repertory encompassed musical comedies and revues, operettas, vaudeville sketches, playlets, ballets, eccentric dancers, acrobats, jugglers, tightrope walkers, and magicians. When the vogue of nudity seized the music halls of Paris in 1894, the Folies elaborated it to such an extent that the theatre’s reputation for sensational displays of female nudity came to overshadow its other performances.

The Folies achieved international repute under the management of Paul Derval (from 1918 to 1966). He staged a series of sumptuous and grandiose spectacles featuring beautiful young women parading in a state of near nudity (despite their gaudy costumes) against exotic backdrops. Parisians and tourists alike were also attracted to the singers, acrobats, and dramatic sketches that made up the rest of the program. The Folies has showcased the talents of many of the great entertainers and music-hall artists of France from the late 19th century on. Among these have been Yvette Guilbert, Mistinguett, Fernandel, Josephine Baker, and Maurice Chevalier.

The Folies-Bergère was managed by Hélène Martini from 1974. Each of its shows requires about 10 months of planning and preparation, 40 different sets, and 1,000 to 1,200 individually designed costumes. The titles of all the Folies’ shows since the late 1880s have each consisted of a total of 13 letters.

This article was most recently revised and updated by Richard Pallardy.Josephine BakerIntroduction & Top QuestionsFast FactsFacts & Related ContentQuizzesMediaImagesMoreMore Articles On This TopicAdditional ReadingContributorsArticle HistoryRelated BiographiesEartha KittEartha KittAmerican musician and actressFlorence MillsFlorence MillsAmerican dancerAudra McDonaldAudra McDonaldAmerican actress and singerJudy Garland, 1945.Judy GarlandAmerican singer and actressSee AllHomeEntertainment & Pop CultureDanceJosephine BakerFrench entertainer Alternate titles: Freda Josephine McDonaldBy The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica • Edit HistoryJosephine BakerJosephine BakerSee all mediaBorn: June 3, 1906 Saint Louis MissouriDied: April 12, 1975 (aged 68) Paris FranceTop QuestionsWho was Josephine Baker?What was Josephine Baker’s early life like?How did Josephine Baker get famous?What awards did Josephine Baker win?Josephine Baker, original name Freda Josephine McDonald, (born June 3, 1906, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.—died April 12, 1975, Paris, France), American-born French dancer and singer who symbolized the beauty and vitality of Black American culture, which took Paris by storm in the 1920s.

Baker grew up fatherless and in poverty. Between the ages of 8 and 10 she was out of school, helping to support her family. As a child Baker developed a taste for the flamboyant that was later to make her famous. As an adolescent she became a dancer, touring at 16 with a dance troupe from Philadelphia. In 1923 she joined the chorus in a road company performing the musical comedy Shuffle Along and then moved to New York City, where she advanced steadily through the show Chocolate Dandies on Broadway and the floor show of the Plantation Club.

Rafael Nadal of Spain celebrates with the championship trophy during the trophy presentation ceremony after winning his Men's Singles final match against Daniil Medvedev of Russia at the 2019 US Open at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center...BRITANNICA QUIZThis Day in History Quiz: June 3Celebrities, politics, and more: How well will you fare on this quiz about June 3?Josephine BakerJosephine Baker© Michael Ochs Archives/Getty ImagesIn 1925 she went to Paris to dance at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in La Revue Nègre and introduced her danse sauvage to France. She went on to become one of the most popular music-hall entertainers in France and achieved star billing at the Folies-Bergère, where she created a sensation by dancing seminude in a G-string ornamented with bananas. She became a French citizen in 1937. She sang professionally for the first time in 1930, made her screen debut as a singer four years later in Zouzou, and made several more films before World War II curtailed her career.

During the German occupation of France, Baker worked with the Red Cross and the Résistance, and as a member of the Free French forces she entertained troops in Africa and the Middle East. She was later awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Résistance. After the war much of her energy was devoted to Les Milandes, her estate in southwestern France, from which she began in 1950 to adopt babies of all nationalities in the cause of what she defined as “an experiment in brotherhood” and her “rainbow tribe.” She adopted a total of 12 children. She retired from the stage in 1956, but to maintain Les Milandes she was later obliged to return, starring in Paris in 1959. She traveled several times to the United States to participate in civil rights demonstrations. In 1968 her estate was sold to satisfy accumulated debt. She continued to perform occasionally until her death in 1975, during the celebration of the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut.

small thistle New from BritannicaONE GOOD FACTCenturies ago, people in Southeast Asia developed a fermented fish sauce called ke-tchup. British traders brought the sauce to England, where variations were made using ingredients like mushrooms and walnuts, until tomato prevailed in the 19th century.See All Good FactsHer life was dramatized in the television movie The Josephine Baker Story (1991) and was showcased in the documentary Joséphine Baker. Première icône noire (2018; Josephine Baker: The Story of an Awakening).

The Editors of Encyclopaedia BritannicaThis article was most recently revised and updated by Patricia Bauer.ErtéIntroductionFast FactsFacts & Related ContentMediaImagesMoreAdditional ReadingContributorsArticle HistoryRelated BiographiesMarc ChagallMarc ChagallBelorussian-born French artistPierre CardinPierre CardinFrench designerMaurice SendakMaurice SendakAmerican artistJosephine BakerJosephine BakerFrench entertainerSee AllHomeEntertainment & Pop CultureMovie, TV & Stage Development & ProductionErtéRussian designer Alternate titles: Romain de TirtoffBy The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica • Edit HistoryErté: evening gownErté: evening gownSee all mediaBorn: November 23, 1892 St. Petersburg RussiaDied: April 21, 1990 (aged 97) Paris FranceMovement / Style: Art DecoErté, byname of Romain de Tirtoff, (born November 23, 1892, St. Petersburg, Russia—died April 21, 1990, Paris, France), fashion illustrator of the 1920s and creator of visual spectacle for French music-hall revues. His designs included dresses and accessories for women; costumes and sets for opera, ballet, and dramatic productions; and posters and prints. (His byname was derived from the French pronunciation of his initials, R.T.)

Erté: dressErté: dress© Sevenarts LimitedErté was brought up in St. Petersburg. In 1912 he went to Paris, where he briefly collaborated with Parisian couturier Paul Poiret. He then became a costume designer and began selling his pen-and-ink and gouache fashion illustrations to American fashion houses. From 1916 to 1937 he was under contract to the American fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar. (A collection of Harper’s Bazaar illustrations was published in Designs by Erté [1976] with text by Stella Blum.) His highly stylized illustrations depicted models in mannered poses draped in luxurious jewels, feathers, and soft, flowing materials against a background of interiors in the Art Deco style.

The same lavish style marked Erté’s theatrical designs. For 35 years he designed elaborately structured opening tableaus, finale scenes, and costumes for the French theatre. He worked for the Folies-Bergère in Paris from 1919 to 1930. During the 1920s he costumed the performers appearing in such American musical revues as the Ziegfeld Follies and George White’s Scandals. In the 1960s Erté produced lithographs, serigraphs, and sheet-metal sculptures. His autobiography, Things I Remember, was published in 1975.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia BritannicaThis article was most recently revised and updated by Amy Tikkanen.music hall and varietyIntroductionFast FactsRelated ContentMoreMore Articles On This TopicContributorsArticle HistoryHomeEntertainment & Pop CultureTheatermusic hall and varietyentertainment By The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica • Edit HistoryKey People: Charlie Chaplin Edith Piaf Josephine Baker Kate Smith May IrwinRelated Topics: minstrel show vaudeville burlesque show saloon gang showmusic hall and variety, popular entertainment that features successive acts starring singers, comedians, dancers, and actors and sometimes jugglers, acrobats, and magicians. Derived from the taproom concerts given in city taverns in England during the 18th and 19th centuries, music hall entertainment was eventually confined to a stage, with the audience seated at tables; liquor sales paid the expenses. To discourage these entertainments, a licensing act was passed in 1751. The measure, however, had the contrary effect; the smaller taverns avoided obtaining licenses by forming music clubs, and the larger taverns, reacting to the added dignity of being licensed, expanded by employing musicians and installing scenery. These eventually moved from their tavern premises into large plush and gilt palaces where elaborate scenic effects were possible. “Saloon” became the name for any place of popular entertainment; “variety” was an evening of mixed plays; and “music hall” meant a concert hall that featured a mixture of musical and comic entertainment.

During the 19th century the demand for entertainment was intensified by the rapid growth of urban population. By the Theatre Regulations Act of 1843, drinking and smoking, although prohibited in legitimate theatres, were permitted in the music halls. Tavern owners, therefore, often annexed buildings adjoining their premises as music halls. The low comedy of the halls, designed to appeal to the working class and to men of the middle class, caricatured events familiar to the patrons—e.g., weddings, funerals, seaside holidays, large families, and wash day.

The originator of the English music hall as such was Charles Morton, who built Morton’s Canterbury Hall (1852) in London. He developed a strong musical program, presenting classics as well as popular music. Some outstanding performers were Albert Chevalier, Gracie Fields, Lillie Langtry, Harry Lauder, Dan Leno and Vesta Tilley.

The usual show consisted of six to eight acts, possibly including a comedy skit, a juggling act, a magic act, a mime, acrobats, a dancing act, a singing act, and perhaps a one-act play.

In the early 20th century music halls were dwarfed by large-scale variety palaces. London theatres, such as the Hippodrome, displayed aquatic dramas, and the Coliseum presented reenactments of the Derby and chariot races of ancient Rome. These were short-lived, but other ambitious plans kept variety prosperous after the real music hall had been killed by the competition of the cinema.

Celebrities such as Sarah Bernhardt, Sir George Alexander, and Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree put on one-act plays or the last acts of plays; musicians such as Pietro Mascagni and Sir Henry Wood gave performances with their orchestras; popular singers of the 1920s, such as Nora Bayes and Sophie Tucker, elicited great enthusiasm; Diaghilev’s ballet, at the height of its fame, appeared in 1918 at the Coliseum on a program that included comedians and jugglers.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.Subscribe Nowsmall thistle New from BritannicaONE GOOD FACTCenturies ago, people in Southeast Asia developed a fermented fish sauce called ke-tchup. British traders brought the sauce to England, where variations were made using ingredients like mushrooms and walnuts, until tomato prevailed in the 19th century.See All Good FactsThe advent of the talking motion picture in the late 1920s caused variety theatres throughout Great Britain to be converted into cinemas. To keep comedians employed, a mixture of films and songs called cine-variety was introduced, and there were attempts to keep theatres open from noon to midnight with nonstop variety. The Windmill Theatre near Piccadilly Circus, London, was notable among the few survivors that remained after World War II from what had been hundreds of music halls. The American equivalent of the British music hall is vaudeville. See also vaudeville.

This article was most recently revised and updated by Amy Tikkanen.theatreIntroductionOrigins of theatre spaceDevelopments in ancient GreeceDevelopments in ancient RomeDevelopments in AsiaThe Middle Ages in EuropeDevelopments of the RenaissanceBaroque theatres and stagingDevelopments in the 19th centuryThe evolution of modern theatrical productionFast Facts2-Min SummaryFacts & Related ContentMediaVideosImagesMoreMore Articles On This TopicAdditional ReadingContributorsArticle HistoryHomeVisual ArtsArchitecturetheatrebuilding Alternate titles: theatronBy Clive Barker See All • Edit HistoryTeatro FarneseTeatro FarneseSee all mediaKey People: Sir John Vanbrugh Aldo Rossi Claude-Nicolas Ledoux Ange-Jacques Gabriel Marcel BreuerRelated Topics: theatre design planetarium amphitheatre showboat prosceniumSummaryRead a brief summary of this topictheatre, also spelled theater, in architecture, a building or space in which a performance may be given before an audience. The word is from the Greek theatron, “a place of seeing.” A theatre usually has a stage area where the performance itself takes place. Since ancient times the evolving design of theatres has been determined largely by the spectators’ physical requirements for seeing and hearing the performers and by the changing nature of the activity presented.

Origins of theatre spaceTaormina, Sicily: theatreTaormina, Sicily: theatreDennis Jarvis (CC-BY-2.0) (A Britannica Publishing Partner)The civilizations of the Mediterranean basin in general, the Far East, northern Europe, and the Western Hemisphere before the voyages of Christopher Columbus in the second half of the 15th century have all left evidence of constructions whose association with religious ritual activity relates them to the theatre. Studies in anthropology suggest that their forerunners were the campfire circles around which members of a primitive community would gather to participate in tribal rites. Karnak in ancient Egypt, Persepolis in Persia, and Knossos in Crete all offer examples of architectural structures, purposely ceremonial in design, of a size and configuration suitable for large audiences. They were used as places of assembly at which a priestly caste would attempt to communicate with supernatural forces.

The transition from ritual involving mass participation to something approaching drama, in which a clear distinction is made between active participants and passive onlookers, is incompletely understood. Eventually, however, the priestly caste and the performer became physically set apart from the spectators. Thus, theatre as place emerged.

Developments in ancient GreeceVisual and spatial aspectsDuring the earliest period of theatre in ancient Greece, when the poet Thespis—who is credited both with inventing tragedy and with being the first actor—came to Athens in 534 BCE with his troupe on wagons, the performances were given in the agora (i.e., the marketplace), with wooden stands for audience seating; in 498, the stands collapsed and killed several spectators. Detailed literary accounts of theatre and scenery in ancient Greece can be found in De architectura libri decem, by the 1st-century-BCE Roman writer Vitruvius, and in the Onomasticon, of the 2nd century CE, by the Greek scholar Julius Pollux. As these treatises appeared several hundred years after classical theatre, however, the accuracy of their descriptions is questionable.

Little survives of the theatres in which the earliest plays were performed, but essential details have been reconstructed from the architectural evidence of the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, which has been remodeled several times since its construction in stone by the politician Lycurgus on the south slope of the Acropolis about 330 BCE. The centre of the theatre was the original dancing place, a flat circular space containing the altar of Dionysus, called the orchestra. In the centre stood a platform with steps (bemata) leading to the altar (thymele). Nearby was the temple out of which the holy image would be carried on festival days so that the god could be present at the plays.

Theatrical representations, not yet wholly free of a religious element, directed their appeal toward the whole community, and attendance was virtually compulsory. Thus the first concern of theatre builders of the day was to provide sufficient space for large audiences. In the beginning, admission was free; later, when a charge was levied, poor citizens were given entrance money. It seems reasonable to assume, from the size of the theatres, that the actors performed on a raised platform (probably called the logeion, or “speaking place”) in order to be more visible and audible, while the chorus remained in the orchestra. In later times there was a high stage, with a marble frieze below and a short flight of steps up from the orchestra. The great Hellenistic theatre at Epidaurus had what is believed to have been a high, two-level stagehouse.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.Subscribe NowThe earliest productions did not have a background building. The actors dressed in the skēnē (from which the word “scene” is derived), which was then a small tent, and the chorus and actors entered together from the main approach, the parodos. The earliest properties, such as altars and rocks, could be set up at the edge of the terrace. The first extant drama for which a large building was necessary was Aeschylus’ trilogy the Oresteia, first produced in 458 BCE. There has been controversy among historians as to whether the skēnē was set up inside a segment of the orchestra or outside the edge of the orchestra. The skēnē in its later development was probably a long, simple building at the left of the orchestra terrace.

In the first period of Greek drama, the principal element of the production was the chorus, the size of which appears to have varied considerably. In Aeschylus’ Suppliants, there were 50 members of the chorus, but in his other plays there were only 12, and Sophocles called for 15. The size of the chorus became smaller in the 5th century, as the ritual element of drama diminished. Since the number of actors increased as the chorus shrank, and the plots of the dramas became more complex, doubling of roles became necessary. On a completely open stage such substitutions were delayed, and the suspense of the drama was dissipated. Dramatic plausibility was also vitiated by the fact that gods and mortals, enemies and friends, always entered from the same direction. The addition of a scenic facade, with three doors, more than doubled the number of entrances and gave the playwright more freedom to develop dramatic tension. About 425 BCE a firm stone basis was laid for an elaborate building, called a stoa, consisting of a long front wall interrupted at the sides by projecting wings, or paraskēnia. The spectators sat on wooden benches arranged in a fan shape divided by radiating aisles. The upper rows were benches of movable planks supported by separate stones planted in the ground. The seats of honour were stone slabs with inscriptions assigning them to the priests.

The background decoration consisted originally of a temporary wooden framework leaning against the front wall of the stoa and covered with movable screens. These screens were made of dried animal skins tinted red; it was not until Aeschylus that canvases in wooden frames were decorated according to the needs of a particular play. Aristotle credits Sophocles with the invention of scene painting, an innovation ascribed by others to Aeschylus. It is notable that Aeschylus took an interest in staging and is credited with the classic costume design. Simple Greek scenery was comparable with that of the 20th century; the impulse to visualize and particularize the background of the action became strong. Painted scenery was probably first used in production of the Oresteia; some 50 years afterward a second story was added to the wooden scene structure. A wooden colonnade, or portico, the proskēnion, was placed in front of the lower story of the building. This colonnade, which was long and low, suggested the exterior of either a house, a palace, or a temple. Painted screens set between the columns of the proskēnion suggested the locale.

In the beginning, scenery was probably altered slightly during the intermissions that separated the plays of a trilogy or a tetralogy or during the night between two festival days. By the latter part of the 5th century, scene changes were accomplished by means of movable painted screens. Several of these screens could be put up behind one another so that, when the first one was removed, the one immediately behind appeared.

Soon after the introduction of the facade, plays were uniformly set before a temple or a palace. To indicate a change of scene, the periaktoi were introduced. These were upright three-sided prisms—each side painted to represent a different locality—set flush with the palace or temple wall on either side of the stage. Several conventions were observed with regard to scenery; one was that if only the right periaktos was turned, it indicated a different locality in the same town. According to another convention, actors entering from the right were understood to be coming from the city or harbour and those from the left to be coming from the country.

The permanent facade was also used to hide the stage properties and the machinery. Evidence for the use of the so-called flying machine, the mēchanē (Latin machina), in the 5th century is given in the comedies of Aristophanes; a character in his play Peace ascends to heaven on a dung beetle and appeals to the scene shifter not to let him fall. The mēchanē consisted of a derrick and a crane. In the time of Euripides it was used conventionally for the epilogue, at which point a god descended from heaven to sort out the complications in the plot, a convention that became known as deus ex machina (“god from a machine”). The lavish use of flying machines is attested by the poet Antiphanes, who wrote that tragic playwrights lifted up a machine as readily as they lifted a finger when they had nothing else to say.

small thistle New from BritannicaONE GOOD FACTCenturies ago, people in Southeast Asia developed a fermented fish sauce called ke-tchup. British traders brought the sauce to England, where variations were made using ingredients like mushrooms and walnuts, until tomato prevailed in the 19th century.See All Good FactsA wheeled platform or wagon, called ekkyklēma, was used to display the results of offstage actions, such as the bodies of murder victims. The ekkyklēma, like the periaktoi, was an expedient for open-air theatre, in which the possibilities for creating realistic illusions were severely limited. A realistic picture of an interior scene under a roof could not be shown, because the roof would block the view of those in the higher tiered seats of the auditorium. So the Greeks, to represent the interior of a palace, for example, wheeled out a throne on a round or square podium. New machines were added in the Hellenistic period, by which time the theatre had almost completely lost its religious basis. Among these new machines was the hemikyklion, a semicircle of canvas depicting a distant city, and a stropheion, a revolving machine, used to show heroes in heaven or battles at sea.

Howard BayClive BarkerGeorge C. IzenourAcousticsMuch recent study has centred on the problem of acoustics in the ancient theatre. The difficulty in achieving audibility to an audience of thousands, disposed around three-fifths to two-thirds of a full circular orchestra in the open air, seems to have been insoluble so long as the performer remained in the orchestra. A more direct path between speaker and audience was therefore essential if the unaided voice was to reach a majority of spectators in the auditorium. Some contend that the acoustical problems were to a degree alleviated when the actor was moved behind and above the orchestra onto the raised platform, with more of the audience thus being placed in direct line of sight and sound with him. By this time, the actors’ masks had reached considerable dimensions, and there are grounds for believing that their mouth orifices were of help in concentrating vocal power—much as cupped hands or a rudimentary megaphone would be.

Increased architectural and engineering sophistication in the Hellenistic Age encouraged further innovations. The theatres of mainland Greece, the Aegean islands, and southern Italy had been constructed in hillsides whenever possible, so that excavation and filling were kept to a minimum; or, lacking a suitable slope, earth was dug out and piled up to form an embankment upon which stone seats were placed. By contrast, the cities of Asia Minor, which flourished during the Hellenistic Age, did not rely on a convenient slope on which to locate their theatres. The principles of arch construction were understood by this time, and theatres were built using vaulting as the structural support for banked seating. Archaeological remains and restoration of theatres at Perga, Side, Miletus, and other sites in what is now Turkey exhibit this type of construction. By a third method, auditoriums were hewed out of rock. Of some six such Greek theatres extant, two excellent examples (both extensively remodeled in Roman times) are the great theatre at Syracuse in Sicily and that at Argos in the Peloponnese. The best preserved of all Greek theatres, also in the Peloponnese and now partially restored, is the magnificent theatre at Epidaurus. This theatre provided seats for some 12,000 people, and its circular orchestra is backed by a stagehouse and surrounded on three sides by a stone, hillside-supported bank of seats. Both chorus and actors performed in the orchestra, but only the actors used the two levels of the stagehouse as well. Theatre construction flourished during the Hellenistic Age as never before in classical times, and no city of any size or reputation was without its theatre.

George C. IzenourDevelopments in ancient RomeThe development of the theatre, following that of dramatic literature, was slower in Rome than in Athens. The essential distinction between Roman and Greek stage performances was that the Roman theatre expressed no deep religious convictions. Despite the fact that the spectacles were technically connected with the festivals in honour of the gods, the Roman audience went to the theatre for entertainment. The circus was the first permanent public building for spectacles, which included chariot races and gladiatorial fights. When Etruscan dancers and musicians were introduced in 364 BCE, they performed in either the circus, the forum, or the sanctuaries in front of the temples. The players brought temporary wooden stands for the spectators. These stands developed into the Roman auditorium, built up entirely from the level ground.

Stage designThe most important feature of the Roman theatre as distinct from the Greek theatre was the raised stage. As every seat had to have a view of the stage, the area occupied by the seating (cavea) was limited to a semicircle. As in Greek theatre, the scene building behind the stage, the scaenae frons, was used both as the back scene and as the actors’ dressing room. It was no longer painted in the Greek manner but tended to have architectural decorations combined with luxurious ornamentation. The audience sat on tiers of wooden benches, spectacula, supported by scaffolding. There was no curtain; the back scene, with its three doors, faced the audience.

When the popular comedies or farces of southern Italy were introduced to Rome, they came with their own distinctive type of stage—the phlyakes stage. Comedies in Italy were mimes, usually parodies of well-known tragedies, and the actors were called phlyakes, or jesters. They used temporary stage buildings of three main forms. One was the primitive low stage, a rough platform with a wooden floor on three or four rectangular posts. The second was a stage supported by low posts, covered with drapery or tablets; sometimes steps led up to a platform and a door was indicated. The third type was a higher stage supported by columns, without steps but usually with a back wall. The stages often had a short flight of five to seven steps in the centre, leading to the podium. The forewall, covered with drapery, was often decorated, and the background wall usually had objects hanging from it. The rear wall sometimes had other columns, besides the ones set at the corners, as well as doors and, in several cases, windows to indicate an upper floor. The door was usually behind a heavily decorated porch, with a sloping or gabled roof supported by beams and cross struts. Among the furnishings there were usually trees, altars, chairs, thrones, a dining table, a money chest, and a tripod of Apollo (i.e., an oracular seat). The stage was set up in the marketplace in the smaller towns and in the orchestras of Greek theatres in the larger cities.

Coincident with the development of the phlyakes stages, and under the inspiration of Hellenistic colonists, the Romans began to build stone theatre buildings. Beginning by remodeling Greek and Hellenistic theatres, they eventually succeeded in uniting architecturally their own concept of the auditorium with a single-level, raised stage. This they did by limiting the orchestra to a half circle and joining it to the auditorium, thereby improving on the acoustics of Greek and Hellenistic theatres. They also brought to perfection the principles of barrel and cross vaulting, penetrating the seat bank at regular intervals with vomitoria (exit corridors). The raised stage was at a single, much lower level than in the Hellenistic theatre. It was roofed, and the number of entrances to it was increased to five: three, as before, in the wall at the rear of the stage and one at each side. The Romans’ love of ostentatious architecture led them to adorn the permanent background with profuse sculptures. In some theatres, a drop curtain was used to signal the beginning and end of performance. In some cases, a canvas roof was hoisted onto rope rigging in order to shade the audience from the sunlight.

Howard BayClive BarkerIn Roman theatres the stage alone was used by the actors, who entered the playing space from one of the house doors or the side entrances in the wings. The side entrance on the audience’s right signified the near distance and the one on the audience’s left the farther distance. If a scene took place in a town, for instance, an actor exiting audience right was understood to be going to the forum; if he exited audience left, he might be going to the country or the harbour. Periaktoi at the side entrances indicated the scenery in the immediate neighbourhood. If the play required a character to move from one house to another without bringing him on the stage, which represented the street, the actor was supposed to use the back door and the angiportum (i.e., an imaginary street running behind the houses). Since interior scenes could not be represented easily, all action took place in front of the houses shown in the background. If a banquet was to be depicted, the table and chairs would be brought on stage and removed at the end of the scene. Costumes were formalized, but real spears, torches, chariots, and horses were used.

The orchestra became part of the auditorium in Rome, reserved by law for those of privileged rank, who seated themselves there on a variety of portable chairs and litters. The orchestra was no longer needed as part of the performance area because the chorus had long since ceased to be an integral part of drama. The tragedies of Seneca, in the 1st century CE, included a chorus because they were patterned after Greek models. But they never achieved the popularity of earlier comedies, especially those of Plautus and Terence. These works had at first been performed on temporary wooden stages that had been erected on a convenient hillside and sometimes surrounded by temporary wooden seating.

Until the late republic, a puritanical Senate had banned all permanent theatre building within the city of Rome itself as decadent. Thus, theatres there were temporary structures, set up in the Campus Martius for the duration of public games. In 55 BCE, however, the triumvir Pompey the Great built Rome’s first permanent stone theatre. Another public stone theatre was built in Rome in 13 BCE and was named after Marcellus, son-in-law of the emperor Augustus. Both were used for the scaenae ludi (“scenic games”), which were part of religious festivities or celebrations of victory in war and which were paid for by triumphant generals and emperors. During the period of the Roman Empire, civic pride demanded that all important cities have theatres, amphitheatres, and, in many instances, a small, permanently roofed theatre (theatrum tectum, an odeum, or music hall) as well. In fact, it is from outlying cities of the empire such as Arausio (Orange), Thamagadi (Timgad), Leptis Magna, Sabratha, and Aspendus that archaeological evidence provides most of the firsthand knowledge of Roman theatre building. The best preserved Roman theatre, dating from about 170 CE, is at Aspendus in modern Turkey.

Vitruvius’ treatise on architectureLiterature is another source for knowledge of Roman theatre. De architectura libri decem (“Ten Books on Architecture”), by the Roman architect Vitruvius (1st century BCE), devotes three books to Greek and Roman theatre design and construction. The author gives general rules for siting an open-air theatre and for designing the stage, orchestra, and auditorium. These rules are based on principles of Euclidian geometry in matters of layout and proportion. His dicta on the provision of good sight lines from auditorium to stage are generally sound. Apart from that, however, his treatise is not very helpful. He mentions changeable scenery but is vague about what was involved. Vitruvius’ notion of acoustics, which he claims is based on theory as well as practice, appears to be vaguely associated with Greek ideas of musical theory but has since been proved to have no scientific or mathematical basis. Indeed, his views on this important matter were to cause problems for almost 2,000 years.

The odeumVitruvius has nothing to say about the roofed odeum (or odeon, “singing place”), which, according to some authorities, represents the high point of theatre building in the ancient world. Theatre history has, unfortunately, largely overlooked these buildings. Excavation work has revealed more than 30 of them, in a wide range of building materials. Odea were apparently first built in Athens under Pericles (5th century BCE). They continued to be built throughout the Hellenistic Age and also in the Roman Empire up to the time of Emperor Severus Alexander (3rd century CE). They range in size from one with a seating capacity of 300–400 to one of 1,200–1,400. Experts disagree as to their specific purpose and use but claim they exhibited a refinement of detail and architectural sophistication found in no other Greco-Roman buildings devoted to the performing arts. They are most often found in Greek cities dating from Hellenistic times, on the grounds of private villas built by Roman emperors from Augustus to Hadrian, and in major cities of the empire, usually dedicated to the emperors. One of the most imposing, which also boasts the greatest span for a wooden trussed roof in the ancient world, was the Odeon of Agrippa, named after the emperor Augustus’ civil administrator. This Roman building in the Athenian agora, dating from about 15 BCE, is beautifully detailed, with an open southern exposure and a truncated curvilinear bank of seating. It achieves an atmosphere of great dignity and repose, despite the vast size of the room. In the last years of the Roman Empire the odeum was, it is claimed, the only remaining home of the performing arts, because by this time open-air theatres had long been given over to sensational and crude popular entertainments.

Greek and Roman theatre building influenced virtually all later theatre design in the Western world, the theatres of the Spanish Golden Age, the English Elizabethan period, and the 20th-century avant-garde, with its experiments in primitive theatre-in-the-round techniques, being exceptions to this pattern. The architectural writings of Vitruvius became the model for the theatre building of the later Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

George C. IzenourClive BarkerDevelopments in AsiaAlthough the emergence of Asian theatre was not simultaneous with that of ancient Greece and Rome, it merits discussion here rather than as an appendage to the history of Western drama.

IndiaIndian theatre is often considered the oldest in Asia, having developed its dance and drama by the 8th century BCE. According to Hindu holy books, the gods fought the demons before the world was created, and the god Brahmā asked the gods to reenact the battle among themselves for their own entertainment. Once again the demons were defeated, this time by being beaten with a flagstaff by one of the gods. To protect theatre from demons in the future, a pavilion was built, and in many places in India today a flagstaff next to the stage marks the location of performances.

According to myth, Brahmā ordered that dance and drama be combined; certainly the words for “dance” and “drama” are the same in all Indian dialects. Early in Indian drama, however, dance began to dominate the theatre. By the beginning of the 20th century there were few performances of plays, though there were myriad dance recitals. It was not until political independence in 1947 that India started to redevelop the dramatic theatre.

In the 4th century a codification was written of the śāstra, or the staging conventions of the dance. It lists not only the costumes, makeup, gestures, and body positions but also any plots considered unsuitable, and it is the most complete document of stagecraft ever compiled. There is no scenery in Indian dance, although there are usually a few properties, such as a three-foot-high brass lamp. A curtain is used, however, by troupes that dance kathākali, an ancient danced drama of southwestern India. The curtain itself is a cloth rectangle that is held between the stage and a large lamp by two stagehands.

Egyptian Book of the Dead: AnubisREAD MORE ON THIS TOPICWestern theatre: The theatreThe outdoor setting for performances of Greek drama traditionally comprised three areas: a large circular dancing floor (orchēstra...The dancers perform a group of preliminary dances behind the curtain until they make an important entrance called “peering over the curtain.” In this, a character fans the lamp by pulling the curtain in and out until the flames are spectacularly high. The dancer, still hiding his face, displays his hands and legs at the borders of the curtain. At the climactic moment the dancer pulls the curtain aside, displaying his awesome makeup, and stagehands remove the curtain until the next dramatic entrance.

Classical Indian drama had as its elements poetry, music, and dance, with the sound of the words assuming more importance than the action or the narrative; therefore, staging was basically the enactment of poetry. The reason that the productions, in which scenes apparently follow an arbitrary order, seem formless to Westerners is that playwrights use much simile and metaphor. Because of the importance of the poetic line, a significant character is the storyteller or narrator, who is still found in most Asian drama. In Sanskrit drama the narrator was the sūtra-dhāra, “the string holder,” who set the scene and interpreted the actors’ moods. Another function was performed by the narrator in regions in which the aristocratic vocabulary and syntax used by the main characters, the gods and the nobles, was not understood by the majority of the audience. The narrator operated first through the use of pantomime and later through comedy.

A new Indian theatre that began about 1800 was a direct result of British colonization. With the addition of dance interludes and other Indian aesthetic features, modern India has developed a national drama. Two examples of “new” theatre staging are the Prithvi Theatre and the Indian National Theatre. The Prithvi Theatre, a Hindi touring company founded in 1943, utilizes dance sequences, incidental music, frequent set changes, and extravagant movement and colour. The Indian National Theatre, founded in Bombay in the 1950s, performs for audiences throughout India, in factories and on farms. Its themes usually involve a national problem, such as the lack of food, and the troupe’s style is a mixture of pantomime and simple dialogue. It uses a truck to haul properties, costumes, and actors; there is no scenery.

ChinaThe most noticeable contrast between China and other Asian countries is that traditionally China has produced virtually no dance. The classic theatre of the Chinese is called “opera” because the dialogue is punctuated with arias and recitatives. Of the amazingly detailed written record of Chinese theatre, the first reference to opera was during the T’ang dynasty (618–907). The development of the opera style popular today took place during the Manchu rule of the 19th century. The Empress Dowager, the last hereditary ruler of China, was so enamoured of opera that she had a triple-deck stage (representing heaven, hell, and earth) constructed in the summer palace at Peking. The most important individual in Chinese theatre of the 20th century, Mei Lan-fang, an actor and producer, was the first to apply scholarship in reviving ancient masterpieces and opera forms.

In general, Chinese theatrical performances start in the early evening and conclude after midnight. The performance itself consists of several plays and scenes from the best known dramas. The audience drinks tea, eats, and talks, and there are no intermissions. The stage itself has a curved apron, covered only by a square rug. On one side is a box for the orchestra, which plays throughout the evening. There is neither a curtain nor any setting to speak of other than a simple, painted backdrop. The virtual absence of scenery accentuates the elaborate and colourful costumes and makeup of the actors.

During a typical performance, the members of a Chinese theatre audience stop talking to each other only at climactic moments. The actors are concerned with their movements only when they are at the centre of the stage; when they stand at the sides they drink tea and adjust their costumes in full view of the audience. An interpretation of this behaviour was the view of the 20th-century German dramatist Bertolt Brecht that a Chinese actor, in contrast to a Western actor, constantly keeps a distance between himself, his character, and the spectator; his performance is mechanistic rather than empathic.

Property men walk around on stage setting up properties for the next play before the preceding one is finished. There are usually very few properties, only a table and a few chairs. A chair may act as a throne, a bench, a tower if an actor stands on it, a barrier if he stands behind it, and so on. A curtain suspended in front of two chairs represents a bed. Doors and stairs are always suggested: an actor mimes opening a door and taking a high step when he “enters” a room.

There are a number of stage conventions; all entrances, for instance, are from a door stage left, and all exits through a door stage right. After a fight scene, the man who is defeated exits first. Wind is symbolized by a man rushing across the stage carrying a small black flag. Clouds painted on boards are shown to the audience to represent either the outdoors or summer. Fire, however, is always represented realistically, either by the use of gunpowder or by pyres of incense. The Chinese feel that Western dramatic realism atrophies the imagination.

JapanJapan is unique in Asia in having a living theatre that retains traditional forms. When an attempt is made in the West to recreate the original production of a Greek tragedy or even a play by Shakespeare, its historical accuracy can only be approximated. In Japan the traditions of stagecraft and costumes for both drama and dance have remained unaltered. Japanese staging developed far earlier than did that of the West; by the time of Shakespeare, for instance, the Japanese had already invented a revolving stage, trapdoors, and complex lighting effects.

Although there are many kinds of theatre in Japan, the best known are the Nō and the Kabuki. Nō was developed by the late 14th century and was first seen by Westerners in the 1850s. It developed from the dengaku, a rice planting and harvesting ritual that was transformed into a courtly dance by the 14th century, and from the sarugaku, a popular entertainment involving acrobatics, mime, juggling, and music, which was later performed at religious festivals.

Two performers and adherents of Zen Buddhism in the late 14th century, Kan’ami and his son Zeami Motokiyo, combined the sarugaku elements with kuse-mai, a story dance that uses both movements and words. Soon dengaku elements were added, and the distinctive Nō style slowly emerged. Like the Zen ways of tea ceremony, ink drawing, and other arts, Nō suggests the essence of an event or an experience within a carefully structured set of rules. There are scores of Nō theatres in Japan today, even though the design of a Nō theatre is so stylized that it is not usable for other types of performances. The Nō stage is a platform completely covered by a curving temple roof. The audience sits on three sides of the stage and is separated from it by a garden of gravel, plants, and pine trees.

Masks are used, though they are restricted to the principal dancer and his companions. The male characters are costumed in brilliant stiff brocades and damasks well suited to the grandiose posturing of the actors. The female roles are played in bright flowered brocades. The outer robes of both sexes are of a fine-woven gauze, light and suitable for the gliding dances when sleeves and fans float in the air. Mask carving is an important art in Japan, and Nō masks add considerable beauty to the traditional robes. Most costumes are based on the classic court hunting dress of the Heian (794–857) and Kamakura (1192–1333) periods.

Kabuki troupes, originally composed only of women, developed in the early 17th century. By the 1680s Kabuki had become an established art form, and curtains and scenery were introduced. Kabuki was first seen in western Europe during the latter part of the 19th century, but it was not until the 1920s that it was accepted there as something more than quaint. The work of the Russian film director Sergey Eisenstein was influenced by the Kabuki troupe that toured the Soviet Union in 1928, and Kabuki staging devices were tried out in theatres in the Soviet Union, France, and Germany; one Kabuki actor, in turn, brought back Russian techniques that influenced the Japanese theatre.

A Kabuki theatre in Tokyo is one of the largest legitimate theatres in the world, with a 91-foot- (28-metre-) wide stage and seating for 2,599 people. Running through the audience and connecting the stage with the rear of the auditorium is the platform runway, called the hanamichi. It is utilized for significant entrances and exits, processions, and dance sequences. Its purpose is to unite the actor and audience by moving the actor out of the decorative background. Originally there were two runways, with a connecting bridge at the rear of the auditorium. Because of economic pressure to seat more people and the influence of Western architecture, the second hanamichi was removed in the early 20th century.

The scenery for Kabuki may be as elaborate and complex as that found anywhere; the stage, for instance, may be a house, a forest, and a river simultaneously. Some settings are triple-level palaces, with the actors using all levels at once; others have only a simple backdrop.

Kabuki costumes are of the Edo period (1603–1868), when Kabuki is considered to have been at its height. Wigs and makeup carefully conform to classical tradition, enabling habitual playgoers to recognize the type of play and characters at a glance. Many of the costumes are much exaggerated; all are designed to accentuate dramatic movement. Courtesans and heroes, for instance, wear stilts that raise them several inches off the ground.

BaliBalinese theatre is included here as representative of theatre in the smaller nations of Asia, such as Thailand, Kampuchea (Cambodia), Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, in all of which drama consists almost exclusively of dance. Balinese dancing may take place anywhere; usually it is executed in front of a temple or a pavilion used for community meetings. The audience sits on three sides of the performers or, occasionally, in the round. The musicians, called the gamelan, sit on one side of the stage area.

There are neither settings nor visible indications of scene changes; location is suggested by the dialogue or the facial expressions and gestures of the actors. A scenic “device” is employed at the beginning of each section of the dance; for instance, the dancer makes a gesture called “opening the curtain.” The hands, palms out, are in front of the face; they separate on a diagonal line to reveal the figure, stopping only when the full, formal posture of Balinese dance is reached.

Howard BayClive BarkerThe Middle Ages in EuropeIn terms of performances and theatres, Roman drama reached its height in the 4th century CE, but it had already encountered opposition that was to lead to its demise. From about 300 CE on, the church tried to dissuade Christians from going to the theatre, and in 401 the fifth Council of Carthage decreed excommunication for anyone who attended performances on holy days. Actors were forofferden the sacraments unless they gave up their profession, a decree not rescinded in many places until the 18th century. An edict of Charlemagne (c. 814) stated that no actor could put on a priest’s robe; the penalty could be banishment. This suggests that drama, most probably mime, had ridiculed the church or that it had tried to accommodate religious sensibilities by performance of “godly” plays.

The invasions of the barbarians from the north and east accelerated the decline of Roman theatre. Although by 476 Rome had been sacked twice, some of the theatres were rebuilt. The last definite record of a performance in Rome was in 533. Archaeological evidence suggests that the theatre did not survive the Lombard invasion of 568, after which state recognition and support of the theatre was abandoned. Theatre did continue for a while in the Eastern Roman Empire, the capital of which was Constantinople, but by 692 the Quinisext Council of the church passed a resolution forofferding all mimes, theatres, and other spectacles. Although the effectiveness of the decree has been questioned, historians until recently used it to signify the end of the ancient theatre.

The assumption now is that although official recognition and support of performances were withdrawn and theatres were not used, some remnants of at least the mime tradition were carried on throughout the Middle Ages. Christian writings suggest that performers were familiar figures. For instance, two popular sayings were “It is better to please God than the actors” and “It is better to feed paupers at your table than actors.” Apart from the mime tradition, one Roman playwright, Terence, retained his reputation through the early Middle Ages, probably because of his literary style.

Howard BayWomen performers were widespread during the period as jugglers, acrobats, dancers, singers, and musicians. There were women troubadours and jongleurs, and many of the French chansons are written from the point of view of female narrators, notably the chansons de mal mariée, or complaints by unhappily married women. Generations of ecclesiastical authorities protested against the great choruses of women who poured into churches and monasteries on feast days, singing obscene songs and ballads. Complaints are recorded from the 6th century CE to the 14th about women taking part in licentious public performances on festive occasions. Women were also active participants in the later mumming plays; the London Mumming circa 1427 was presented by an all-female cast, while in the Christmas Mumming at Hertford the young king Henry VI saw a performance consisting of “a disguysing of the rude upplandisshe people compleynynge on hir wyves, with the boystous aunswere of hir wyves.”

Church theatreMedieval religious drama arose from the church’s desire to educate its largely illiterate flock, using dramatizations of the New Testament as a dynamic teaching method. It is doubtful whether there is any connection between the drama of classical times and the new rudimentary dramatizations that slowly grew into the miracle and mystery cycles of plays in the Middle Ages. As early as the 10th century in Switzerland, France, England, and Germany, short and simple dramatic renderings of parts of the Easter and Christmas liturgy of the mass were being performed. As these short scenes grew in number, small scenic structures, called mansions, sedum, loci, or domi (the Latin words for seats, places, and homes, respectively), were placed at the sides of the church nave. At these were acted stories of the Nativity, Passion, or Resurrection, depending upon the particular season of the Christian calendar. At the conclusion of each scene the congregation turned its attention to the next mansion, so following a succession of scenes set out at intervals around the nave. Gradually, the performance of liturgical drama passed out of the hands of the clergy and into those of the laity, probably via the trade guilds of craftsmen, which were also religious fraternities. More and more secular interludes crept into the dramas—to such an extent that the dramas moved out of the church building into the public square. The individual plays became linked in cycles, often beginning with the story of the creation and ending with that of the Last Judgment. Each play within the cycle was performed by a different trade guild. Many of the plays from different cycles have survived and can still be seen in parts of England.

George C. IzenourClive BarkerStaging conventionsA number of staging conventions that evolved in the church were to continue throughout the Middle Ages. Apart from the mansions there was a general acting area, called a platea, playne, or place. The methods of staging from these first liturgical dramas to the 16th-century interludes can be divided into six main types. The first involved the use of the church building as a theatre. In the beginning, for Easter tropes (embellishments of the liturgy), a tomb was set up in the north aisle. As dialogue was added, the entire nave was used, and within this space different localities were indicated by mansions. A few mansions housed numerous elaborate properties, particularly those for the Last Supper. Some mansions had curtains so that characters or objects might be revealed at a particular moment or concealed at the end of an episode. Sometimes the choir loft was used to represent heaven and the crypt to represent hell.

The second type of staging evolved by the 12th century, as drama began to outgrow the capacity of the church to contain it. As long as the action was confined to the central theme, it could be played in an arrangement of mansions down the length of the nave. But as the subject matter extended to include both Old and New Testament history, the action was transferred to a stage outside the west door of the church. In 1227 Pope Gregory IX decreed the removal of what had become a show from holy ground to the marketplace or an open field. During the same period the language of the plays began to change from Latin to the vernacular. When drama was first taken outdoors, the crucifix was placed at one end, no doubt where it would have appeared above the altar in the church. Mansions were placed alongside each other, usually in sequences reflecting earlier church performances.

A third type of staging was the so-called stationary setting, found outside of England, which involved placing the mansions in a wider range of locales. Here the audience accepted three conventions. One was the symbolic representation of localities by the mansions; the second was the placing of the mansions near each other; and the third was the use for acting purposes of such actual ground as was enclosed by or in front of each mansion. The mansions were placed in either a straight or a slightly curved line, and all of the scenery was visible simultaneously. Because of their scope, many of the plays were divided into parts separated by intermissions ranging from one to 24 hours. During the intermissions, mansions were changed. Also, some mansions might represent more than one location; the identity of the mansions was announced before each segment of a play. It is difficult to know exactly how many mansions were used; in a play at Lucerne, Switz., in 1583, for instance, 70 different locations were indicated, though only about 32 mansions were actually used.

The two mansions almost always present were those representing heaven and hell, set at opposite ends of the playing area. The earthly scenes were set in the middle, and the two opposing mansions were supposed to represent man’s dual nature and the choices that faced him. In the 15th and 16th centuries, heaven was usually raised above the level of the other mansions. Sometimes heaven had a series of intricate turning spheres, from which emanated the golden light of concealed torches. The hell mansion was designed to be the complete opposite of that of heaven; some portions of it, for instance, were below stage level. Sometimes hell was made to look like a fortified town, an especially effective image when Jesus Christ forced open the gates to free the captive souls. The entrance to hell was usually shaped like a monster’s head and was called Hell’s Mouth, emi