When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

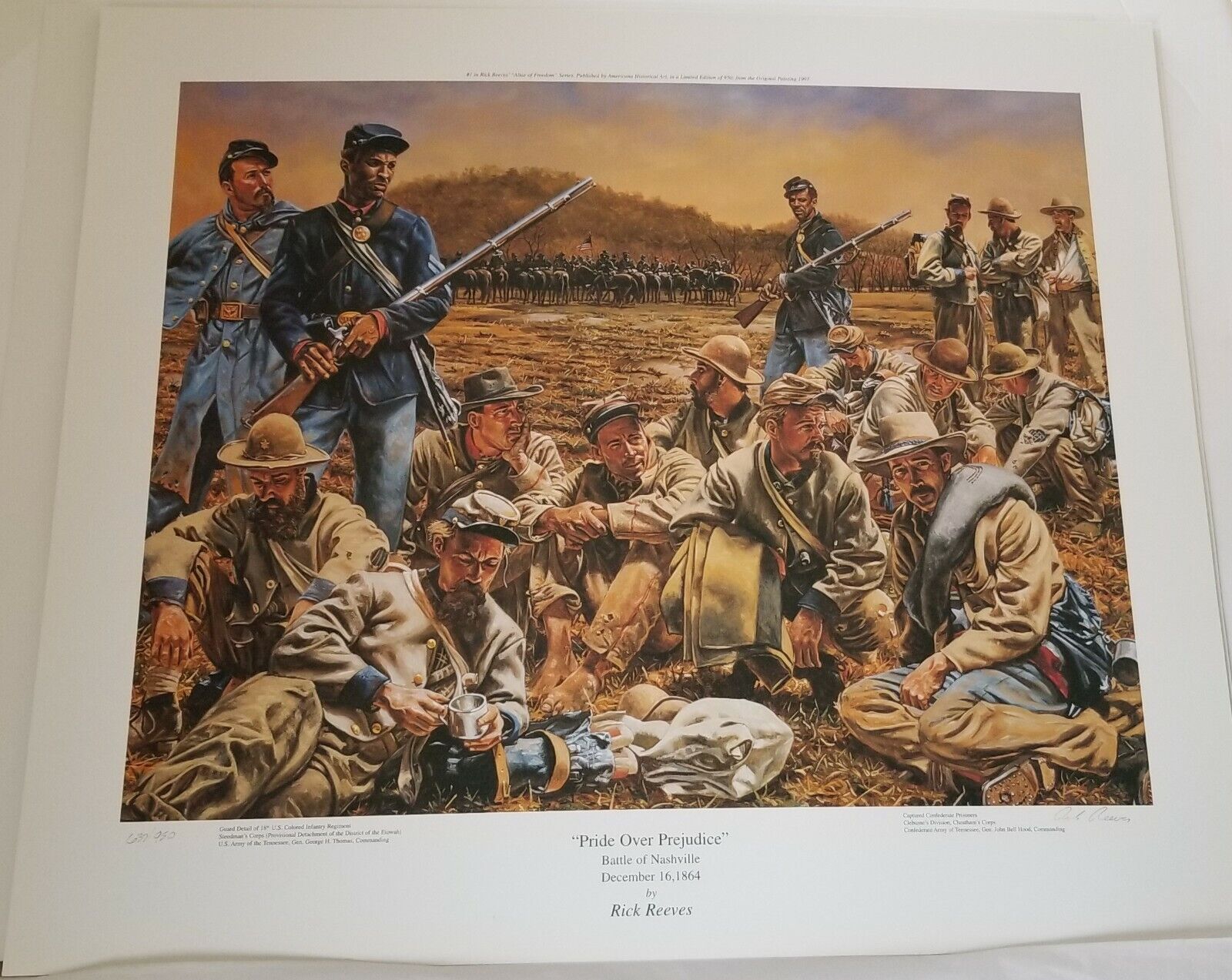

PRIDE OVER PREJUDICE - BATTLE OF NASHVILLE DEEMBER 16, 1864 by Rick Reeves. Signed, numbered, limited edition art print. Limited to only 950 in the edition. Mint condition with certificate of authenticity. Number may be different than the one pictured. Insured USPS delivery in the continental US. Originally sold for $ 150.00. Measures 26" x 22".

PRIDE OVER PREJUDICEA Civil War Historical Narrativeby Major George E. Reynolds

President Abraham Lincoln concluded his December 1, 1862 Message to Congress by stating in part: "In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free - honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best, hope on earth." Under fire from rival Democrats and some members of his own Republican Party, the embattled Lincoln wrote those forthright words just one month before the formal signing of his Emancipation Proclamation. With the passage of that remarkable document, President Lincoln made perpetually free the nearly four million slaves living in bondage within the territories of the rebellious Confederate States of America.

Although historically speaking it was the Confiscation Act of July 1862 that first specifically authorized black enlistment, Lincoln refused to allow the policy until after his signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Some of Lincoln's more abolitionist minded generals, however, attempted to raise their own black units prior to the official go-ahead.

General John Fremont, commander of Union forces in Missouri, issued a directive freeing all slaves in his area of operations without first getting the President's approval and in nearby Kansas, Brigadier General Jim Lane formed black units without the War Department's concurrence. Northern officers like Generals David Hunter and Rufus Saxton in South Carolina tried to form black regiments from the multitudes of contrabands that fled across Union lines. While in Louisiana, General Benjamin Butler mustered into service the free men of color of the Louisiana Native Guards - thereafter known as the Corps d' Afrique. Those efforts, though, were limited in scope and the full and advantageous impact of African American recruitment was not fully realized until after the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Emancipation Proclamation dramatically changed forever, the direction of the American Civil War. With one mighty stroke of his pen, Lincoln transformed the war from one waged to restore the Union, to one fought to abolish the evil of Southern slavery. Lincoln's important declaration also paved the way for the official authorization and the raising of African American regiments to augment the already war-weary white Union forces. This audacious move proved to be a political powder keg for Lincoln. To many Northerners, the President's action was tantamount to treason; large numbers of outspoken citizens and politicians were alarmed and appalled at the prospects of black recruits. Arguing against the black enlistment bill, one Democratic legislator declared: "This is a government of white men, made by white men for white men, to be administered, protected, defended, and maintained by white men."

Reacting sharply to the outrageous and offensive claims against his policy, an acerbic and unmoved Lincoln argued that peace would eventually come to the Union, and when it did: "Then, there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it."

Unfortunately, the strong debate over black enlistment was not limited to Northern civilian sectors and political arenas. Numerous white soldiers, enlisted men and officers alike, strongly objected to the idea of African American military service, contending that blacks had no place fighting in a "white man's war." One private in a Rhode Island infantry regiment no doubt spoke for many when he wrote: "The plan of having Negro soldiers is very well in some cases; but when it comes to putting the whites and blacks on the same footing, I come to the conclusion it is about time to quit soldiering. I want to see the war come to a close, this rebellion crushed, and the Stars and Stripes waving over a united country once more, and I am willing to fight for it, but I am not willing to fight shoulder to shoulder with a black."

Fortunately for the Union, prejudicial attitudes amongst Northerners was not universal. Abolitionists rejoiced in Lincoln's decision while scores of others, reluctantly, if not pragmatically, accepted the idea of black enlistment. One Ohio lieutenant surely echoed the thoughts of others when he wrote: ".. there is not a Negro in the army that is not a better man than a rebel .." And in another example of in-ranks support for the President's plan, Union Captain Charles Hill wrote his wife saying: "A great many white people have the idea that the entire Negro race are vastly their inferiors. I have a more elevated opinion of their abilities than ever before. I know that many of them are vastly the superiors of those who would condemn them to a life of brutal degradation."

President Lincoln also found a strong ally - and at times harsh critic - in the renowned African American orator and anti-slavery advocate Frederick Douglass. Douglass was an eloquently vocal supporter of black enlistment and was one of the earliest leaders to understand that a black call to arms was the quickest and surest means available to gain African American respect and equality. Realizing the important need for black men to participate in the achievement of their own freedom, Douglass proclaimed: "The colored man only waits for honorable admission into the service of the country. They know that who would be free must strike the first blow."

The South, for its part, erupted in sweeping, and for the most part frenzied, outrage over the Lincoln edict. Confederate President Jefferson Davis, along with just about every other rebel political and social leader, vehemently condemned the idea of black enlistment and promoted it as "last ditch measure" of a defeated Northern government. The Confederate Congress responded quickly, and on May 1, 1863 passed a formal declaration that black men bearing arms would be viewed as insurrectionary slaves subject to the laws of the states where they were captured. At the very least, captured African American soldiers faced a return to the shackles of bondage. In numerous documented instances, however, surrendering black soldiers along with their white officers were killed outright by their Confederate captors. Rebel soldiers had little tolerance for a policy that exposed turning former slaves into soldiers.

It was into this bubbling cauldron of social and political turmoil that President Abraham Lincoln plunged, first himself, and then the entire nation. Understanding full well the profound positive impact African American soldier manpower would have on the Union war effort and the devastating psychological jolt it would produce within Confederate ranks, Lincoln ordered the formation of black regiments. Writing to then Tennessee Governor Andrew Jackson in March, 1863, a poised Lincoln professed: "The colored population is the great available, yet unavailed of, force for restoring the Union. The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once."

The - great available colored population - that Lincoln wrote of responded overwhelmingly, and with little haste, to his call to the Nation's defense. Inspired by vigorous support from prominent black leaders and motivated by African American newspapers emblazoned with phrases like: "We must fight! fight! fight!"; "It is now or never - now if ever."; "What better field to claim our rights than the field of battle?"; "To strike for the Union, is to strike for the bondsmen,." blacks descended upon recruiters in large numbers.

While many of the would be enlistees lining up outside of the bustling recruitment stations were recently liberated slaves or plantation runaways, a much larger number were black men who were born free. Men like George Stephens of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania who implored: "We do not deserve the name of freemen, if we disregard the teachings of the hour and fail to place in the balance against oppression, treason, and tyranny, our interests, our arms, and our lives." Stephens, who served in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, went on to add: "we have more to gain, if victorious, or more to lose, if defeated, than any other class of men, (the) sooner we awaken to their inexorable demands upon us, the better for the race, the better for the country, the better for our families, and the better for ourselves." Another member of the famed 54th, Corporal James Henry Gooding, passionately encouraged black volunteerism by writing:

"As one of the race, I beseech you, slavery must die! It depends on the black men of the North, whether it will die or not - those who are in bonds must have some one to open the door; when slaves see the white soldier approach, he dares not trust him and why? Because he has heard that some have treated him worse than their owners in the rebellion. But if the slave sees the black soldier, he knows that he has got a friend; and through friendship, he that was once a slave can be made a soldier, to fight for his own liberty. Now is the time to act!"

White leaders, also heralding the cause of black recruitment, zealously solicited and encouraged black men to enlist. None was more enthusiastic in effort than Massachusetts Republican Governor John A. Andrew. Andrew had long and ardently advocated the use of blacks in the military - fully believing that they could, and would fight if given the opportunity. It was no surprise then, when he, along with the earnest support of Frederick Douglass - raised the nation's first post-Emancipation Proclamation black unit, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.

When the proud and imposing 54th paraded along Boston Common in grand review on May 28,1863, they knew that a pugnacious rebel enemy awaited them in South Carolina. The magnificent men of the noble regiment refused to yield to the uncertainty of their impending fate, however, and instead marched triumphantly amongst the cheering and flag waving well-wishers - both black and white - who lined the crowded streets. The impressive 54th departed the Bay State as the model for all of the black regiments that followed.

All total, some 185,000 African American men followed in the exalted footsteps of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, hell-bent on confirming their manhood and extinguishing the flames of Southern oppression. A staggering 74% of all free blacks of military age (18-45) fought for their country. They formed into 166 units - 60 of which engaged in direct combat - and organized as 145 infantry regiments, 13 artillery units, seven cavalry groups, and one engineer battalion. Most of the units mustered into service with state designated titles - 55th Massachusetts; 1st Kansas; 1st Mississippi - until the War Department changed the names to the United States Colored Troops (USCT) in 1864. Even then, four units - 5th Massachusetts Cavalry; 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry; 29th Connecticut Infantry - retained their state designations throughout the entire war.

All of the black units - except for the Corps d' Afrique - entered military service led by white officers. This was done to assuage the concerns and help stem the objections of many Northerners who opposed black enlistment. Unfortunately for the soldiers, though, many officer selections were not based on qualifications. Thus black regiments became convenient dumping grounds for careless, self-promoting, or just plain inferior officers.

These substandard officers were many times inept and usually racist and the unlucky black soldiers almost always paid the price. On more than one occasion, black soldiers were carelessly thrown into a deadly maelstrom of fire by commanders who didn't know any better or who just didn't care. Luckily, however, the majority of USCT units were led by well qualified officers who fit Governor Andrew's designs for: "young men of military experience, of firm anti-slavery principles, ambitious, superior to vulgar contempt for color, and having faith in the capacity of colored men for military service."

The white leadership issue notwithstanding, black also faced many others problems in their passage from civilian to soldier. Often th ey received second-rate equipment, shoddy clothing, inadequate supplies, and inferior living environments - not to mention a pervasive cloud of prejudice that existed throughout the military ranks. These indignities were minor, however, when compared to the explosive issue of equal pay.

In 1863, when blacks began to enlist, the pay for white recruits was $13 per day plus food and clothing. All concerned, including the War Department, assumed that the new black soldiers would be entitled to equal payment as well. Instead, Solicitor William Whiting, using requirements specified in the Militia Act of 1862 ruled that soldiers of the USCT would be paid at the black government laborer rate of $10 per day; deducting another $3 for a clothing allowance.

Needless to say, blacks were universally inflamed by the blatant display of discrimination. Many soldiers refused to accept their pay rather than suffer the indignation. One disgruntled soldier argued his point effectively when he asked: "Do we not fill the same ranks? Do we not cover the same ground? Do we not take up the same length of ground in the graveyard as others do? The ball does not miss the black man and strike the white, they strike one as much as the other, we have done a soldier's duty, why can't we have a soldier's pay?"

Eventually in 1864, Washington politicians bowed to pressure from blacks and whites alike and reinstated equal pay measures; to some, however, the unjust policy forever stigmatized the legitimacy of the Federal government's intentions.

Despite these tremendous adversities and many other stifling acts of bias, black soldiers took to the field of battle with a level of intensity and ferocity no less than that of their white comrades at arms. Against the parapets of Battery Wagner, along the approaches to Port Hudson, within the trenches of Petersburg, and across the many other battlefields were they spilled their precious blood, black soldiers completely destroyed the myths of slavery. Their gallant deeds garnered twenty-nine Medals of Honor and all but erased the skepticism of an entire nation. By their heroic conduct, they vindicated their manhood, and earned forever, the rightful claim to citizenry in the United States of America.

In the words of one white officer following the overwhelming Union victory at Nashville, Tennessee: "I have often heard men say that they would not fight beside a Negro soldier but on the 16th the whites and blacks charged together and they fell just as well as we did. When you hear any one say that Negro soldiers wont fight just tell them that, I have seen a great many fighting for our country."

Just as pointed, but more solemnly stated, was 28th USCT chaplain Garland H. White, who proudly proclaimed: "The historian pen cannot fail to locate us somewhere among the good and the great, who have fought and bled upon the altar of their country."